In my first article on the measles outbreaks in the Pacific Northwest, I argued that measles vaccination rates have declined little since 1995. Here I’d like to expand on that idea, and comment on specific claims made by various sources.

Is the Washington Post Right?

"Clark County Public Health Director Alan… https://t.co/xVudNNxURM

— Dr. Richard Pan (@DrPanMD) February 7, 2019

Twitter seems to have stored a clip that cannot be found in the actual article being linked to in Dr. Pan’s tweet, so I am including it here. According to the summary, “lax state laws have helped drive down vaccination rates across the pacific Northwest.” What the article does state is the following.

The Pacific Northwest is home to some of the nation’s most vocal and organized anti-vaccination activists. That movement has helped drive down child immunizations in Washington, as well as in neighboring Oregon and Idaho, to some of the lowest rates in the country, with as many as 10.5 percent of kindergartners statewide in Idaho unvaccinated for measles. That is almost double the median rate nationally.

So is the article being truthful? Well, I’d say it’s an “alternative fact.” Consider the following graphs.

Washington State Vaccination Rates

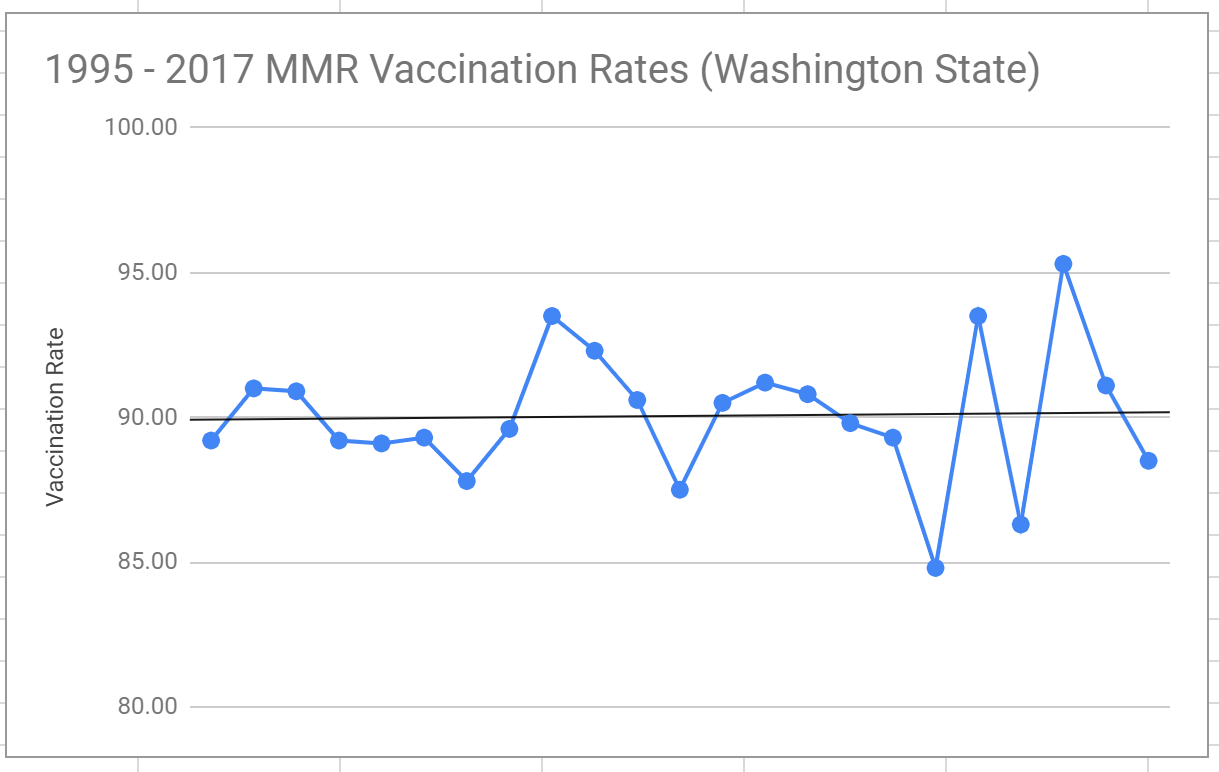

I gave an overall analysis of immunization rates at the HHS region and state levels, in my first article. But I want to go into a little more detail about Washington State’s vaccination rates. First off, in the last couple of years, there’s been a rise in volatility, but it’s hard to tell whether this rise is out of the ordinary. When people cite such a short length of time and argue that there’s been a “decline” in vaccination rates, it’s no better than when people look at a few years of cold winters and say “look, the Earth is cooling!” A proper analysis does not look at a few data points. It looks at how those data points compare to the overall known data set.

This graph shows the volatility in the last few years. And perhaps there’s something in the 2012 blip, however it doesn’t seem to be enough to explain the timing of the outbreak, especially since overall vaccination rates are a an average of annual rates. That means that year-by-year variations are smoothed over multiple years.

Better Data Needed

In order to make any more conclusions, a lot more data will be needed. Pockets may be on the county level, or the nodes may be even smaller. If that’s the case, there could still be a change in distribution that my analyses aren’t capturing. But if that’s the case, then it doesn’t seem reasonable that they’d be having such an impact on larger scale outbreaks. We can think of very small communities, within a very large population, almost as individuals.

A Serendipitous Experiment has come out of these recent outbreaks. According to Ars Technica, the recent spike in cases, and widespread attention and concern, has caused a massive increase in vaccinations. So not only should we see an increase in vaccination rates in the coming data sets, but we should see a decline in pockets as well.

Now, the issue is that even if source of the recent outbreaks is something other than the antivax sentiment, we should see a decline in cases, because the vaccine does a good job at preventing symptoms. And that’s why we should ensure that vaccination rates are high. But this result also will cloud any data. A proper analysis would therefore have to adjust for changes in vaccination, if the goal is to see if perhaps the pathogen is becoming more virulent.

Asymptomatic Infection Analysis

Especially because of the recent outbreak and rapid changes in vaccination rates among certain populations, now is the time to take action in analyzing asymptomatic infections. As I’ve mentioned in my paper on whooping cough, asymptomatic infections are poorly understood and studied. While there are certainly differences between whooping cough and measles, and their associated vaccinations, there’s still something we should see, if we took a random sample of the population: infection rates should be significantly lower among vaccinated individuals than in unvaccinated individuals. And how different they are can give us greater insight into how well the current vaccine is working to stop the measles infection.

To give some insight into what we could find, I recently came across a paper studying measles vaccination in Taiwan, presented to me as justification for current understanding of measles vaccination. What the person failed to notice is that based on a random sampling of the population, rather than a survey of cases, it seems that the basic reproduction rate is not driven below one, suggesting an inability to generate herd immunity. One reason that I use “seems” is that I’m currently trying to double check with the authors to see if this was an estimate in the case of 100% vaccination or not.

The disconnect between the apparent “eradication” of measles in the United States, and the general recognition by the medical community that a 95% vaccination rate should generate herd immunity, may suggest that asymptomatic infection is indeed a problem. And that’s why we really need to do a wide-scale analysis in the United States.