The following is a paper on the historical nature of Bede. It is relevant to other historical and psuedo-historical documents, including the Bible. It’s been converted from .docx format, so there may be some errors. This may later be extended into a more robust paper on the nature of history.

In his presidential address R.W. Southern argued that medieval historians did not simply view a historical event as the result of prior events, but rather as the result of divine intervention[1]. At first glance, this does seem to be the correct understanding, but looking deeper, it turns out that in at least some cases, this is far from the truth. One such example is Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People. On the surface, Bede’s History does appear theological. First and foremost, it was a work commissioned to address the history of the Christian church in England; a significant amount of the wording appears to be theological; and there are multiple references to divine intervention and miraculous events. Yet it is possible to show that most of his work is a proper history. In fact, if we allow for two forms of historical discourse, then it can be shown that the entire work is indeed a proper history. The two forms of history that I will address, in relationship to Bede’s History, are “scientific history,” and history from the internal perspective of a culture, or as it might be called “emic history.”

The first question that must be answered is “what constitutes a proper history?” This is a difficult question to answer, and has been debated for a long time. I will present what I consider to be a proper history, and then show that Bede’s work falls in line with one of two forms of proper history. In medieval historiography, we have three general formats for historical information. The first is the annals format. The second is the chronicles format. And the third is the narrative format.

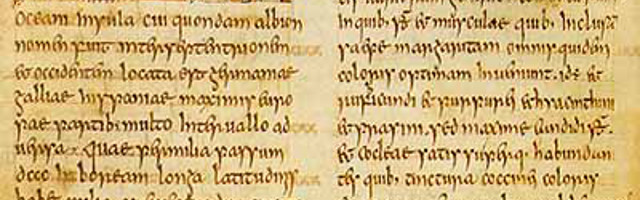

The annals format is the simplest of the three historical formats. It is simply a roster of dates and events which occurred during those dates. As an example, the Annals of Saint Gall lists “720. Charles fought against the Saxons[2].” Nothing surrounding that time period addresses the causes or the consequences. It event just was. The chronicle format is somewhat more robust. While still listed in a roster format overall, years 977 and 982 from the Abingdon Manuscript show many entries with more detailed expression and literary completeness. 982 even gives a sequence of events involving Otto, Rome’s emperor at the time, going to battle in Greece[3].

So why then are neither the annals format nor the chronicles format proper histories? First, there are three layers to history. There is the written record of events: the who, what, where, and when; there is the why and how; and there is a summary of these first two, which relate the information to the reader in a meaningful way. A history which only includes the first part is simply incomplete. Second, from its very origin, history has largely centered around the eyewitness. Two prime quotes on the importance of eye witness accounts in history come from M. I. Finley, an ancient historian. These quotes are “unless a generation is captured on paper and the framework of its history fixed, either contemporaneously or soon thereafter, the future historian is for ever blocked” and “unless something is captured in a more or less contemporary historical account, the narrative is lost for all time.”[4] So it is the eye witness, who initially takes an event occurring in the world, and translates it into human knowledge. So, if the eyewitness account itself is not available, there must at least be some attempt to track the genealogy of that knowledge, from the initial eyewitness, down to the historian. Neither the annals form nor the chronicle form include any attempt to map such a genealogy.

But even when all of these elements are present, history can take a variety of forms. One form is the “scientific history.” And, if we are to treat history as a science, then we need a body of theories to accompany the raw listing of historical conditions. These theories must act to explain the conditions present at a given point of history, based on the prior conditions and events, they must be self consistent and consistent with the raw listing of historical conditions, and there must be a way to falsify a false theory, by finding additional information that would contradict the theory. That would make the theory a scientific one, at least if we use the basic formulation proposed by Karl Popper in The Logic of Scientific Discovery.

This formulation requires its own set of assumptions. Just as science in general assumes a natural explanation for that which is being researched, it is assumed that historical conditions are the consequence of other historical conditions, rather than something which is separate from the historical realm. A full argument for this definition of science is beyond the scope of this paper, but if such a formulation of science is is accepted as valid, then it can be shown that Bede’s History is indeed a proper history.

This view is also essentially consistent with Hayden White’s position on narrative discourse and historical representation, except that even though White views scientific attempts at history to be devoid of narrative, the narrative that White describes is more or less the theory component of a historical work[5]. Both the annals and the chronicles formats are lacking in this component, but Bede’s work does exhibits a fully developed narrative or theory connecting historical events.

This is true with other forms of science as well. Our raw data might include the geological record and we might have various sub theories on radiometric dating, etc, but all of this comes together in complete theory or narrative on how Earth came to be what it is today. Essentially, narrative allows us to convey the meaning of the outcomes of scientific investigation and to explain the current state of our understanding of the scientific view of reality. So there is no contradiction between the requirement for narrative in history and a desire to formalize it into a science.

There is a question of whether or not any given history is required to have a detailed exposition, or whether or not the narrative is sufficient to convey the information in a scientific way. There is a great deal of scientific material which does not concern itself with expressing, in detail, the fundamental mechanics, but which would still be considered reasonably scientific. These works coexist with the more rigorous and yet more mechanical body of scientific papers.

Berlin is concerned that history lacks the formal scaffolding that recognized sciences have. But no science exists in a vacuum. Biology relies on chemistry and physics, and chemistry itself relies heavily on physics. Such is also the case with history. It relies on the mechanics from the other social sciences: anthropology, sociology, political science, economics, and so on. While it is true that we cannot simply posit that “whenever or wherever [x] then or there [y][6]” we do not need to concern ourselves with such deterministic models. Most of the social sciences have this issue, in part because humans behave in a very stochastic way. In fact, there are even natural sciences which suffer from this. Meteorology and climatology are two examples. If we were worried about absolute certainty and precision in defining a science, we would not be able to consider either of these two fields of research sciences.

Now, if history, even in a scientific form, requires a narrative, then it requires a subject. White suggests that such a subject, if existing at all, in incomplete histories such as the annals, is “the Lord.” But a god is beyond the realm of scientific investigation. It was then, and it is now. So what is the subject of the narrative in Bede’s work? The answer is “man.” That is the subject of all history. “History is an account of what men have done and of what has happened to them[7].” This helps us place history in a specific category of sciences. It is specifically a social science.

Because we have a larger body of scientific evidence and theory now, than we had during Bede’s life, valid historical theory would have been less restrictive. We now have multiple ways of estimating the dates of events and analyzing the validity of claims about the past. Such methods include tree ring dating, the geological theory of superposition, and radiometric dating.

Modern historians would often exclude any event which involves miracles and religious activity. In other words, the modern historian excludes from the record, any report of events related to religion, including visions and other miracles. But does including a listing of such miracles place a document outside of the realm of a “true history?” It does not have to. It seems that as long as the causal relationships between events in history are empirically justifiable, then it does not matter if there is additional information. And this additional information should be included, if your source is including them in a retelling of events. Otherwise the eyewitness account is incomplete.

With at least a discussion of scientific history out of the way, it is now possible to analyze most of Bede’s work, but in order to classify much of Bede’s as scientific history, certain linguistic anomalies should be addressed. Much of the religious tone of the work can be explained as linguistic in nature, rather than truly religious. Furthermore, given the nature of the work—a history of the church—many of the sources would have accepted religious phenomenon as being real. Bede, if truly impartial, would still have been relying on recounts of events, as viewed by devoutly religious people, who would not have rejected a religious phenomenon has being true. Only if Bede was partial against such accounts would his history have excluded them.

While a word or phrase may have a theological connotation in some instances, in many others the usage may simply be idiomatic. Two potential examples of are the use of phrases like “year of the lord” and the apparent reference to divine intervention in the conversion of Alban to Christianity.

References to the “year of the lord” and years before or after the “incarnation of our lord”, while referencing a theological construct, also identify a secular reality: the number of years before or after a reference point. Even today, we have not completely eliminated the usage. Even with the shift away from A.D. and B.C. and towards C.E. and B.C.E. we still use the exact same reference point as a marker. This is true, whether or not we believe in “the incarnation of our lord.” Furthermore, because Bede was specifically writing the ecclesiastical history of the English people, the birth of Christ would have been a logical reference point, regardless of whether Christ was a truly divine figure.

Similarly, references to divine intervention may simply be idiomatic. Bede mentions “the grace of god” when addressing the conversion of Alban to Christianity[8]. However, is is truly a suggestion that there was divine intervention, or simply a reference to luck, much as someone might say “god willing” in modern vernacular?

The use of terms such as “year of the lord”, as well as references to apparent divine intervention, in Bede’s History do appear to be theological interpretations of history at first glance, but upon further consideration, they can also be viewed as idiomatic expressions, borrowed from the religious lexicon, and used in a secular fashion. Therefore, while it is possible that Southern is correct in his analysis of medieval historiography, there is certainly an argument counting it as well.

In at least some cases, linguistic analysis can exonerate Bede of violations of scientific history. But some accounts cannot be explained by mere linguistics. Even still, there are other potential issues which may be examples of violations. We must address bias in Bede’s writing, degree of citation of sources, and inclusion of references to theological events.

Bede is clearly biased in his work. There is a goal to writing his Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Bede admits this in his preface: “if history records good things of good men, the thoughtful hearer is encouraged to imitate what is good: or if it records evil of wicked men, the devout, religious listener or reader is encouraged to avoid all that is sinful and perverse and to follow what he knows knows to be good and pleasing to God[9].” However, bias does not invalidate a historical document any more than it does any other scientific work. Indeed, there is very often a goal in scientific investigation. Researchers are often paid to conduct research on products, economists often have a preference for economic theories, and so on. What matters is that the methodology itself is sound, and that their biases are made known, as was done in the case of the Bede’s History.

As for citation, strict citation was not exactly a requirement during the medieval period, and still may be lacking in many history books. However, the better the citation the better the sources can be vetted. Whenever we rely on a source’s information about historical events, we are making assumptions about the validity of their reports. Even if there is an implicit assumption that the factual information is correct, and we can begin cutting back on facts that are self contradictory, there is an added level of comfort that is provided by having a trustworthy source. But even this suggests that Bede’s work is a fairly solid example of a history. At the very beginning of his work, Bede assures Ceolwulf, who requested the History to be written, that the information is accurate. He does this by citing authorities including Abbot Albinus, Abbot Hadrian, as well as various letters of various Popes, and various earlier historians[10]. In Book IV Chapter 25, when discussing the destruction of Coldingham monastery, Bede provides his source: his “fellow-priest Edgils, who was living in the monastery at the time.[11]” Therefore there is at least some level of genealogical information present.

Bede was describing the history of the church, and that so many of the people of the time would have been Christian, accounts of miracles and other similar events would have been common to find in his source material. Can we reconcile the references to clearly theological aspects within the History? The distinction between theological claims by the author and theological claims by the characters of the history is important. If this is material passed on from others, the material itself would be pre-filtered in a religious way. If what was professed to be seen was a religious act, or dragons, or anything of that nature, then it wouldn’t be that Bede and other medieval historians would necessarily be filtering, or reinterpreting stories using a specifically theological lense, but that they would fail to reject that which was told to them, just because it was religious.

In such instances, Bede is including the emic perspective, while still maintaining the scientific form of history. There is certainly utility in this. After all, the way in a person interprets a series of events can drastically influence how he reacts to them, and therefore can help to explain the causal relationship between those events and future events. A modern example would be George W. Bush’s view that god told him to end the tyranny in Iraq[12]. Whether or not there was any divine intervention or not, Bush’s belief that god had instructed him in this way had an impact on the decision to go to war. If a historian ignored this internal theological interpretation, the causes of the Iraq war would be clouded.

In Book II Chapter 12, Bede references a discussion between Edwin and another man, during his time in exile, in which future events were foretold by a spirit. But a question arises. Was Bede claiming that Edwin saw a spirit, or was the claim of a historical character? Bede himself never states that divine intervention saved Edwin. Instead he expresses it as what was told by others: “Hereupon, it was said, he vanished, and Edwin realized that it was not a man but a spirit who had appeared to him[13].”

However, even then, these visions do not lead Edwin to conversion, nor did the words of Paulinis. Instead Edwin spent many hours pondering the matter[14]. It is only after the discussions with his advisors does he choose to convert, and much of the discussion was utilitarian in nature, focusing on what the old religion has not done for the people, and what the new religion might be able to do[15]. This suggests that there is, at the very least, a greater emphasis on historical causality than there is on divine intervention.

Perhaps one of the most difficult chapters to reconcile is chapter seven of book four. It seems to be a clear indication of divine events. And it really is. However, these are retellings of eye witness accounts. It’s a listing of miracles which were purported to have happened at the covent. It is the nun’s conclusion that the light was of divine nature and that it was a message of where to be buried. It was not Bede’s. This is very similar to the realization that Edwin had in Book II Chapter 12. These divine interaction are expressed as interpretations of the historical figures, rather than of the historian.

So it can be seen that at least much of Bede’s History is indeed a scientific history. However, not all history needs to be scientific, and there are a few parts of the work that fail the requirements necessary to be a scientific one. Even then a few rules should still hold. At the very least, the history should still be self consistent and consistent not with science, but with other internal ways of thinking in a given culture, and should do a reasonable job of documenting the genealogical origin of the information expressed in the history. An internal history, which does not rely on scientific impartiality would essentially be the emic perspective, or the internal perspective as expressed by the historian.

There are a few passages that cannot be reconciled. This includes Book III Chapter 15 and Book IV Chapter 25. In III-15, there is a direct reference to actions of god, and while Bede almost saves himself by citing the genealogy of the story, he still oversteps as a scientific historian by using his own voice, rather than the voice of Cynimund et. al.[16] In IV-25, Bede addresses his desire to include the discussion of the fire at Coldingham to “warn the reader of the workings of God…[17]” Still because the genealogy is present, and because there is no contradiction with anything else that was said in the history, III-15 and IV-25 are still a valid examples of emic history. III-16 is similar. Bede concludes that the royal city was “so clearly under God’s protection.” While a bit unclear of just who “those in a position to know the facts” are, sources are at least again addressed, and so we have our genealogy[18]. Furthermore, in the case of IV-25, Bede clearly stated his bias, rather than leaving it hidden.

One way to emphasize the nature of a proper history is to contrast it with an improper one. Because the topic of discussion connected to theological works, the best example of an invalid history would probably be the bible. While there are elements of the bible which do seem to be historical, the bible fails as a proper history in a few ways. First, it is not self consistent. This can be seen by looking at Genesis. The order of creation differs between Genesis 1 and Genesis 2. Specifically, the order of events in which humans and animals were created differ, with man—Adam—being created after animals in Genesis 1 and before animals in Genesis 2. A further issue is that god, angels, etc are characters in the bible. There are numerous cases of God directly influencing the course of events, and angels speaking directly to people. These characters are theological, not historical. Genesis is again an example of this in that it addresses god’s actions directly. God spoke. God created. This excludes it from being either a scientific history or an emic history.

While logical consistency and the nature of the characters in the work are vital, what does not matter is whether or not the events are true. We now have evidence that the entire battle of Jericho did not occur. At the time that the Israelites entered Jericho, the area had been abandoned[19]. But that a history has since been contradicted, does not mean that it is an invalid history.

So, the bible fails to be either a scientific history or an emic history, but what about other works? During the medieval period, the epic was a very popular format, and the most well known epic of the era was probably Beowulf. Robert W. Hanning addresses Beowulf as a “heroic history.” However, does Beowulf exist as a proper history? Unfortunately it not only fails scientific history, but even emic history. The key component which is missing from Beowulf is the genealogy of information. There are no sources. This does not mean that it is not of interest to the modern historian or anthropologist. Epics can give us insight into the way in which people of the era thought, but that does not mean that it is reasonable to call them histories. As Hanning points out, the Epic indicates that hagiography was of considerable importance to the people of the time[20].

While Bede does include a great deal of content from religious people, and this has resulted in the Ecclesiastical History of the English People appearing to be a highly theological work, due to the way in which he incorporated the reports of miraculous events, his refrain from citing divine figures as historical ones, and taking into account vernacular, it is now apparent that the work is closer to a proper history than to a theological work, with a few exceptions. But even ignoring those few exceptions, the work is still one that gives modern historians pause, in part because modern historians automatically exclude miracles from accounts and because, in modern times, we have a larger body of scientific theory, with which historical accounts must be reconciled, than had existed during Bede’s lifetime. But we must not view Bede’s History as improper, just because of this fact. If we did so, we would also have to conclude that almost all past scientific works are not ”proper science” because they contradict modern theory and evidence. Furthermore, when taking into account those parts which fail to be scientific history, the remainder is still valid etic history, as it remains self consistent, takes into account genealogy of information, and provides a full narrative explaining not just the who, what, where, and why, but also the why and how.

End Notes

- Southern, R. W. “Presidential Address: Aspects of the European Tradition of Historical Writing 1.The Classical Tradition from Einhard to Geoffrey of Monmouth.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 20 (1970) ↑

- Hayden White, The Content of Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990). ↑

- Viking Sources in Translation: Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Abingdon MS,accessed November 21, 2016, https://classesv2.yale.edu/access/content/user/haw6/Vikings/AS%20Chronicle%20Abingdon%20MS.html. ↑

- Megan Bishop Moore, Philosophy and Practice in Writing a History of Ancient Israel, 37 ↑

- Ibid. 6 ↑

- Berlin Concepts and Categories, 112 ↑

- Berlin, Isaiah. “History and Theory: The Concept of Scientific History.” History and Theory 1, no. 1 (1960): 1-31, doi: 10.2307/2504255. ↑

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, (Penguin Classics; Revised edition, 1991), 51. ↑

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, 41. ↑

- Ibid., 41-43 ↑

- Ibid., 253 ↑

- George Bush: ‘God told me to end the tyranny in Iraq’ | World news | The Guardian, accessed October 25, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/oct/07/iraq.usa. ↑

- Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, 127 ↑

- Ibid., 128 ↑

- Ibid., 129 – 131 ↑

- Ibid., 167 – 168. ↑

- Ibid., 253 ↑

- Ibid., 168 ↑

- William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Wm. B.Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2003), 46. ↑

- Robert W. Hanning, “Beowulf as Heroic History.” Medievalia et Humanistica 5 (1974), 80. ↑

Bibliography

Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, (Penguin Classics; Revised edition, 1991).

Berlin, Isaiah. “History and Theory: The Concept of Scientific History.” History and Theory 1, no. 1 (1960): 1-31, doi: 10.2307/2504255.

Hanning Robert W., “Beowulf as Heroic History.” Medievalia et Humanistica 5 (1974)

Hayden White, The Content of Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990).

George Bush: ‘God told me to end the tyranny in Iraq’ | World news | The Guardian, accessed October 25, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/oct/07/iraq.usa.

Moore, Megan B., Philosophy and Practice in Writing a History of Ancient Israel, (T&T Clark; 1 edition, 2009).

Sharan B. Merriam and Tisdell, Elizabeth J. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, (Jossey-Bass; 4 edition, 2015).

Southern, R. W. “Presidential Address: Aspects of the European Tradition of Historical Writing 1. The Classical Tradition from Einhard to Geoffrey of Monmouth.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 20 (1970): 173-96. doi:10.2307/3678767.

Viking Sources in Translation: Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Abingdon MS, accessed November 21, 2016, https://classesv2.yale.edu/access/content/user/haw6/Vikings/AS%20Chronicle%20Abingdon%20MS.html.